There are more than 20,000 species of wild bees. Many species are solitary (e.g., Mason bees), and many others rear their young in burrows and small colonies, (e.g., bumblebees). Beekeeping, or apiculture, is concerned with the practical management of the social species of honey bees, which live in large colonies of up to 100,000 individuals. In Europe and America the species universally managed by beekeepers is the Western honey bee (Apis mellifera). This species has several sub-species or regional varieties, such as the Italian bee (Apis mellifera ligustica ), European dark bee (Apis mellifera mellifera), and the Carniolan honey bee (Apis mellifera carnica). In the tropics, other species of social bee are managed for honey production, including Apis cerana.

All of the Apis mellifera sub-species are capable of inter-breeding and hybridizing. Many bee breeding companies strive to selectively breed and hybridize varieties to produce desirable qualities: disease and parasite resistance, good honey production, swarming behaviour reduction, prolific breeding, and mild disposition. Some of these hybrids are marketed under specific brand names, such as the Buckfast Bee or Midnite Bee. The advantages of the initial F1 hybrids produced by these crosses include: hybrid vigor, increased honey productivity, and greater disease resistance. The disadvantage is that in subsequent generations these advantages may fade away and hybrids tend to be very defensive and aggressive.

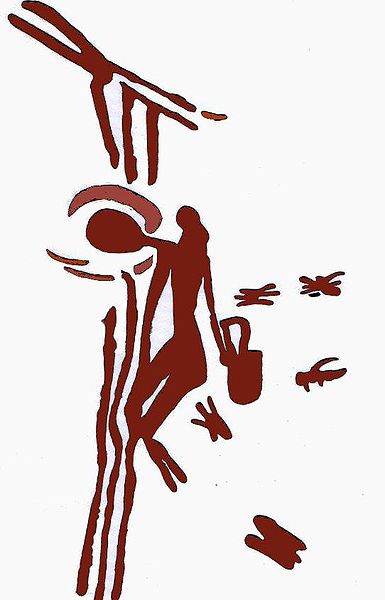

Wild honey harvesting

Collecting honey from wild bee colonies is one of the most ancient human activities and is still practiced by aboriginal societies in parts of Africa, Asia, Australia, and South America. Some of the earliest evidence of gathering honey from wild colonies is from rock paintings, dating to around 13,000 BCE. Gathering honey from wild bee colonies is usually done by subduing the bees with smoke and breaking open the tree or rocks where the colony is located, often resulting in the physical destruction of the nest location.

Domestication of wild bees

At some point humans began to attempt to domesticate wild bees in artificial hives made from hollow logs, wooden boxes, pottery vessels, and woven straw baskets or “skeps”. Honeybees were kept in Egypt from antiquity. On the walls of the sun temple of Nyuserre Ini from the 5th Dynasty, before 2422 BCE, workers are depicted blowing smoke into hives as they are removing honeycombs. Inscriptions detailing the production of honey are found on the tomb of Pabasa from the 26th Dynasty (c. 650 BCE), depicting pouring honey in jars and cylindrical hives. Sealed pots of honey were found in the grave goods of Pharaohs such as Tutankhamun.

In prehistoric Greece (Crete and Mycenae), there existed a system of high-status apiculture, as can be concluded from the finds of hives, smoking pots, honey extractors and other beekeeping paraphernalia in Knossos. Beekeeping was considered a highly valued industry controlled by beekeeping overseers — owners of gold rings depicting apiculture scenes rather than religious ones as they have been reinterpreted recently, contra Sir Arthur Evans.

Archaeological finds relating to beekeeping have been discovered at Rehov, a Bronze and Iron Age archaeological site in the Jordan Valley, Israel. Thirty intact hives, made of straw and unbaked clay, were discovered by archaeologist Amihai Mazar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in the ruins of the city, dating from about 900 BC. The hives were found in orderly rows, three high, in a manner that could have accommodated around 100 hives, held more than 1 million bees and had a potential annual yield of 500 kilograms of honey and 70 kilograms of beeswax, according to Mazar, and are evidence that an advanced honey industry existed in ancient Israel 3,000 years ago. Ezra Marcus, an expert from the University of Haifa, said the finding was a glimpse of ancient beekeeping seen in texts and ancient art from the Near East.

In ancient Greece, aspects of the lives of bees and beekeeping are discussed at length by Aristotle. Beekeeping was also documented by the Roman writers Virgil, Gaius Julius Hyginus, Varro, and Columella.

The art of beekeeping appeared in ancient China for a long time and hardly traceable to its origin. In the book “Golden Rules of Business Success” written by Fan Li (or Tao Zhu Gong) during the Spring and Autumn Period there are some parts mentioning the art of beekeeping and the importance of the quality of the wooden box for bee keeping that can affect the quality of its honey.

The ancient Maya domesticated a separate species of stingless bee.

The Beekeepers, 1568, by Pieter Bruegel the ElderIt

Study of honey bees

was not until the 18th century that European natural philosophers undertook the scientific study of bee colonies and began to understand the complex and hidden world of bee biology. Preeminent among these scientific pioneers were Swammerdam, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, Charles Bonnet, and the blind Swiss scientist Francois Huber. Swammerdam and Réaumur were among the first to use a microscope and dissection to understand the internal biology of honey bees. Réaumur was among the first to construct a glass walled observation hive to better observe activities within hives. He observed queens laying eggs in open cells, but still had no idea of how a queen was fertilized; nobody had ever witnessed the mating of a queen and drone and many theories held that queens were “self-fertile,” while others believed that a vapor or “miasma” emanating from the drones fertilized queens without direct physical contact. Huber was the first to prove by observation and experiment that queens are physically inseminated by drones outside the confines of hives, usually a great distance away.

Following Réaumur’s design, Huber built improved glass-walled observation hives and sectional hives that could be opened like the leaves of a book. This allowed inspecting individual wax combs and greatly improved direct observation of hive activity. Although he went blind before he was twenty, Huber employed a secretary, Francois Burnens, to make daily observations, conduct careful experiments, and keep accurate notes over more than twenty years. Huber confirmed that a hive consists of one queen who is the mother of all the female workers and male drones in the colony. He was also the first to confirm that mating with drones takes place outside of hives and that queens are inseminated by a number of successive matings with male drones, high in the air at a great distance from their hive. Together, he and Burnens dissected bees under the microscope and were among the first to describe the ovaries and spermatheca, or sperm store, of queens as well as the penis of male drones. Huber is universally regarded as “the father of modern bee-science” and his “Nouvelles Observations sur Les Abeilles (or “New Observations on Bees”) revealed all the basic scientific truths for the biology and ecology of honeybees.

Invention of the movable comb hive

Rural beekeeping in the 16th century

Early forms of honey collecting entailed the destruction of the entire colony when the honey was harvested. The wild hive was crudely broken into, using smoke to suppress the bees, the honeycombs were torn out and smashed up — along with the eggs, larvae and honey they contained. The liquid honey from the destroyed brood nest was crudely strained through a sieve or basket. This was destructive and unhygienic, but for hunter-gatherer societies this did not matter, since the honey was generally consumed immediately and there were always more wild colonies to exploit. But in settled societies the destruction of the bee colony meant the loss of a valuable resource; this drawback made beekeeping both inefficient and something of a “stop and start” activity. There could be no continuity of production and no possibility of selective breeding, since each bee colony was destroyed at harvest time, along with its precious queen.

During the medieval period abbeys and monasteries were centers of beekeeping, since beeswax was highly prized for candles and fermented honey was used to make alcoholic mead in areas of Europe where vines would not grow. The 18th and 19th centuries saw successive stages of a revolution in beekeeping, which allowed the bees themselves to be preserved when taking the harvest.

Intermediate stages in the transition from the old beekeeping to the new were recorded for example by Thomas Wildman in 1768/1770, who described advances over the destructive old skep-based beekeeping so that the bees no longer had to be killed to harvest the honey. Wildman for example fixed a parallel array of wooden bars across the top of a straw hive or skep (with a separate straw top to be fixed on later) “so that there are in all seven bars of deal” [in a 10-inch-diameter (250 mm) hive] “to which the bees fix their combs.” He also described using such hives in a multi-storey configuration, foreshadowing the modern use of supers: he described adding (at a proper time) successive straw hives below, and eventually removing the ones above when free of brood and filled with honey, so that the bees could be separately preserved at the harvest for a following season. Wildman also described a further development, using hives with “sliding frames” for the bees to build their comb, foreshadowing more modern uses of movable-comb hives. Wildman’s book acknowledged the advances in knowledge of bees previously made by Swammerdam, Maraldi, and de Réaumur — he included a lengthy translation of Réaumur’s account of the natural history of bees — and he also described the initiatives of others in designing hives for the preservation of bee-life when taking the harvest, citing in particular reports from Brittany dating from the 1750s, due to Comte de la Bourdonnaye.

The 19th Century saw this revolution in beekeeping practice completed through the perfection of the movable comb hive by Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth, a descendant of Yorkshire farmers who emigrated to the United States. Langstroth was the first person to make practical use of Huber’s earlier discovery that there was a specific spatial measurement between the wax combs, later called the bee space, which bees do not block with wax, but keep as a free passage. Having determined this bee space (between 5 and 8 mm, or 1/4 to 3/8″), Langstroth then designed a series of wooden frames within a rectangular hive box, carefully maintaining the correct space between successive frames, and found that the bees would build parallel honeycombs in the box without bonding them to each other or to the hive walls. This enables the beekeeper to slide any frame out of the hive for inspection, without harming the bees or the comb, protecting the eggs, larvae and pupae contained within the cells. It also meant that combs containing honey could be gently removed and the honey extracted without destroying the comb. The emptied honey combs could then be returned to the bees intact for refilling. Langstroth’s classic book, The Hive and Honey-bee, published in 1853, described his rediscovery of the bee space and the development of his patent movable comb hive.

passage. Having determined this bee space (between 5 and 8 mm, or 1/4 to 3/8″), Langstroth then designed a series of wooden frames within a rectangular hive box, carefully maintaining the correct space between successive frames, and found that the bees would build parallel honeycombs in the box without bonding them to each other or to the hive walls. This enables the beekeeper to slide any frame out of the hive for inspection, without harming the bees or the comb, protecting the eggs, larvae and pupae contained within the cells. It also meant that combs containing honey could be gently removed and the honey extracted without destroying the comb. The emptied honey combs could then be returned to the bees intact for refilling. Langstroth’s classic book, The Hive and Honey-bee, published in 1853, described his rediscovery of the bee space and the development of his patent movable comb hive.

The invention and development of the movable-comb-hive fostered the growth of commercial honey production on a large scale in both Europe and the USA (see also Beekeeping in the United States).

Lorenzo Langstroth (1810-1895)

Evolution of hive designs

Langstroth’s design for movable comb hives was seized upon by apiarists and inventors on both sides of the Atlantic and a wide range of moveable comb hives were designed and perfected in England, France, Germany and the United States. Classic designs evolved in each country: Dadant hives and Langstroth hives are still dominant in the USA; in France the De-Layens trough-hive became popular and in the UK a British National Hive became standard as late as the 1930s although in Scotland the smaller Smith hive is still popular. In some Scandinavian countries and in Russia the traditional trough hive persisted until late in the 20th Century and is still kept in some areas. However, the Langstroth and Dadant designs remain ubiquitous in the USA and also in many parts of Europe, though Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France and Italy all have their own national hive designs. Regional variations of hive evolved to reflect the climate, floral productivity and the reproductive characteristics of the various subspecies of native honey bee in each bio-region.

The differences in hive dimensions are insignificant in comparison to the common factors in all these hives: they are all square or rectangular; they all use movable wooden frames; they all consist of a floor, brood-box, honey super, crown-board and roof. Hives have traditionally been constructed of cedar, pine, or cypress wood, but in recent years hives made from injection molded dense polystyrene have become increasingly important.

Hives also use queen excluders between the brood-box and honey supers to keep the queen from laying eggs in cells next to those containing honey intended for consumption. Also, with the advent in the 20th century of mite pests, hive floors are often replaced for part of (or the whole) year with a wire mesh and removable tray.

Pioneers of practical and commercial beekeeping

The 19th Century produced an explosion of innovators and inventors who perfected the design and production of beehives, systems of management and husbandry, stock improvement by selective breeding, honey extraction and marketing. Preeminent among these innovators were:

Jan Dzierżon, was the father of modern apiology and apiculture. All modern beehives are descendants of his design.

L. L. Langstroth, revered as the “father of American apiculture”, no other individual has influenced modern beekeeping practice more than Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth. His classic book The Hive and Honey-bee was published in 1853.

Moses Quinby, often termed ‘the father of commercial beekeeping in the United States’, author of Mysteries of Bee-Keeping Explained.

Amos Root, author of the A B C of Bee Culture, which has been continuously revised and remains in print. Root pioneered the manufacture of hives and the distribution of bee-packages in the United States.

A.J. Cook, author of The Bee-Keepers’ Guide; or Manual of the Apiary, 1876.

Dr. C.C. Miller was one of the first entrepreneurs to actually make a living from apiculture. By 1878 he made beekeeping his sole business activity. His book, Fifty Years Among the Bees, remains a classic and his influence on bee management persists to this day.

Major Francesco De Hruschka was an Italian military officer who made one crucial invention that catalyzed the commercial honey industry. In 1865 he invented a simple machine for extracting honey from the comb by means of centrifugal force. His original idea was simply to support combs in a metal framework and then spin them around within a container to collect honey as it was thrown out by centrifugal force. This meant that honeycombs could be returned to a hive undamaged but empty, saving the bees a vast amount of work, time, and materials. This single invention greatly improved the efficiency of honey harvesting and catalysed the modern honey industry.

Walter T. Kelley was an American pioneer of modern beekeeping in the early and mid-20th century. He greatly improved upon beekeeping equipment and clothing and went on to manufacture these items as well as other equipment. His company sold via catalog worldwide and his book, How to Keep Bees & Sell Honey, an introductory book of apiculture and marketing, allowed for a boom in beekeeping following World War II.

In the U.K. practical beekeeping was led in the early 20th century by a few men, pre-eminently Brother Adam and his Buckfast bee and R.O.B. Manley, author of many titles, including ‘Honey Production In The British Isles’ and inventor of the Manley frame, still universally popular in the U.K. Other notable British pioneers include William Herrod-Hempsall and Gale.

In India, R.N.Mattoo was the pioneer worker in starting beekeeping with Indian honeybee, Apis cerana indica in early 1930s. Beekeeping with European honeybee, Apis mellifera was started by Dr. A.S.Atwal and his team members, O.P.Sharma and N.P.Goyal in Punjab in early 1960s.It remained confined to Punjab and Himachal Pradesh up to late 1970s. Later on in 1982, Dr. R.C.Sihag, working at Haryana Agricultural University,Hisar (Haryana), introduced and established this honeybee in Haryana and standardized its management practices for semi-arid-subtropical climates.On the basis of these practices, Beekeeping with this honeybee could be extended to the rest of the country. Now beekeeping with Apis mellifera predominates in India.

Traditional beekeeping

Fixed comb hives

A fixed comb hive is a hive in which the combs cannot be removed or manipulated for management or harvesting without permanently damaging the comb. Almost any hollow structure can be used for this purpose, such as a log gum, skep or a clay pot. Fixed comb hives are no longer in common use in industrialised countries, and are illegal in some places that require inspection for problems such as varroa and American foulbrood. In many developing countries fixed comb hives are widely used and because they can be made from any locally available material are very inexpensive and appropriate. Beekeeping using fixed comb hives is an essential part of the livelihoods of many communities in poor countries. The charity Bees for Development recognises that local skills to manage bees in fixed comb hives are widespread in Africa, Asia and South America.

Modern beekeeping

Movable frame hives

In the United States, the Langstroth hive is commonly used. The Langstroth was the first successful top-opened hive with movable frames, and other designs of hive have been based on it. Langstroth hive was however a descendant of Jan Dzierzon’s Polish hive designs. In the United Kingdom, the most common type of hive is the British National Hive, which can hold Hoffman, British Standard or popular Manley frames, but it is not unusual to see some other sorts of hive (Smith, Commercial and WBC, rarely Langstroth). Straw skeps, bee gums, and unframed box hives are now unlawful in most US states, as the comb and brood cannot be inspected for diseases. However, straw skeps are still used for collecting swarms by hobbyists in the UK, before moving them into standard hives.

Top-bar hives

A growing number of amateur beekeepers are adopting various top-bar hives similar to the type commonly found in Africa. Top bar hives were originally used as traditional beekeeping a method in both Greece and Vietnam. These have no frames and the honey-filled comb is not returned to the hive after extraction, as it is in the Langstroth hive. Because of this, the production of honey is likely to be somewhat less than that of a Langstroth hive. Top bar hives are mostly kept by people who are more interested in having bees in their garden than in honey production per se. Some of the most well known top-bar hives are the Kenyan Top Bar Hive (KTBH) with sloping sides, the Tanzanian Top Bar Hive, which has straight sides and the Vertical Top Bar Hives such as the Warre or “People’s Hive” designed by Abbe Warre in the mid 1900s.

The initial costs and equipment requirements are far lower. Often scrap wood or #2 or #3 pine is able to be used with a nice hive as the outcome. Top-bar hives also offer some advantages in interacting with the bees and the amount of weight that must be lifted is greatly reduced. Top-bar Hives are being widely used in developing countries in Africa and Asia as a result of the Bees for Development program. There is a growing number of beekeepers in the U.S. using various top-bar hives within the past 2 years or so.

Protective clothing

Beekeepers often wear protective clothing to protect themselves from stings

While knowledge of the bees is the first line of defense, most beekeepers also wear some protective clothing. Novice beekeepers usually wear gloves and a hooded suit or hat and veil. Experienced beekeepers sometimes elect not to use gloves because they inhibit delicate manipulations. The face and neck are the most important areas to protect, so most beekeepers wear at least a veil.

Defensive bees are attracted to the breath, and a sting on the face can lead to much more pain and swelling than a sting elsewhere, while a sting on a bare hand can usually be quickly removed by fingernail scrape to reduce the amount of venom injected.

The protective clothing is generally light colored (but not colorful) and of a smooth material. This provides the maximum differentiation from the colony’s natural predators (bears, skunks, etc.), which tend to be dark-colored and furry.

‘Stings’ retained in clothing fabric continue to pump out an alarm pheromone that attracts aggressive action and further stinging attacks. Washing suits regularly, and rinsing gloved hands in vinegar minimizes attraction.

Bee smoker with heat shield and hook

Smoke is the beekeeper’s third line of defense. Most beekeepers use a “smoker” — a device designed to generate smoke from the incomplete combustion of various fuels. Smoke calms bees; it initiates a feeding response in anticipation of possible hive abandonment due to fire. Smoke also masks alarm pheromones released by guard bees or when bees are squashed in an inspection. The ensuing confusion creates an opportunity for the beekeeper to open the hive and work without triggering a defensive reaction. In addition, when a bee consumes honey the bee’s abdomen distends, supposedly making it difficult to make the necessary flexes to sting, though this has not been tested scientifically.

Smoke is of questionable use with a swarm, because swarms do not have honey stores to feed on in response. Usually smoke is not needed, since swarms tend to be less defensive, as they have no stores to defend, and a fresh swarm has fed well from the hive.

Many types of fuel can be used in a smoker as long as it is natural and not contaminated with harmful substances. These fuels include hessian, twine, burlap, pine needles, corrugated cardboard, and mostly rotten or punky wood. Indian beekeepers, especially in Kerala, often use coconut fibers as they are readily available, safe, and of negligible expense. Some beekeeping supply sources also sell commercial fuels like pulped paper and compressed cotton, or even aerosol cans of smoke. Other beekeepers use sumac as fuel because it ejects lots of smoke and doesn’t have an odor.

Some beekeepers are using “liquid smoke” as a safer, more convenient, alternative. It is a water-based solution that is sprayed onto the bees from a plastic spray bottle.

Torpor may also be induced by the introduction of chilled air into the hive – while chilled carbon dioxide may have harmful long-term effects.

Effects of stings and of protective measures

Some beekeepers believe that the more stings a beekeeper receives, the less irritation each causes, and they consider it important for safety of the beekeeper to be stung a few times a season. Beekeepers have high levels of antibodies (mainly IgG) reacting to the major antigen of bee venom, phospholipase A2 (PLA). Antibodies correlate with the frequency of bee stings.

The entry of venom into the body from bee-stings may also be hindered and reduced by protective clothing that allows the wearer to remove stings and venom sacs with a simple tug on the clothing. Although the stinger is barbed, a worker bee is less likely to become lodged into clothing than human skin.

Natural beekeeping

There is a current movement that eschews chemicals in beekeeping and believes that health issues in bees can most effectively be addressed by reversing trends that disrespect the needs of the bees themselves. Crop spraying, unnatural conditions in which bees are moved thousands of miles to pollinate commercial crops, frequent opening of the hive for inspection, artificial insemination of queens, routine medication and sugar water feeding are all thought to contribute to a general weakening of the constitution of the honey bee.

Practitioners of ‘natural beekeeping’ tend to use variations of the top-bar hive, which is a simple design that retains the concept of movable comb without the use of frames or foundation. The horizontal top-bar hive, as championed by Marty Hardison, Michael Bush, Philip Chandler, Dennis Murrell and others, can be seen as a modernization of hollow log hives, with the addition of wooden bars of specific width from which bees hang their combs. Its widespread adoption in recent years can be attributed to the publication in 2007 of The Barefoot Beekeeper by Philip Chandler, which challenged many aspects of modern beekeeping and offered the horizontal top-bar hive as a viable alternative to the ubiquitous Langstroth-syle movable-frame hive.

The most popular vertical top-bar hive is probably the Warré hive, based on a design by the French priest Abbé Émile Warré (1867–1951) and popularized by Dr. David Heaf in his English translation of Warré’s book L’Apiculture pour Tous as Beekeeping For All.

Natural beekeeping is characterized by a willingness to hand most of the control to the bees themselves, and to minimize interference in their lives. Practitioners expect to take honey only when the bees’ needs have first been taken care of, and the feeding of sugar is discouraged except as an emergency measure.

Urban or backyard beekeeping

Main article: urban beekeeping

Related to natural beekeeping, urban beekeeping is an attempt to revert to a less industrialized way of obtaining honey by utilizing small-scale colonies that pollinate urban gardens. Urban apiculture has undergone a renaissance in the 2000s (decade), and urban beekeeping is seen by many as a growing trend; it has recently been legalized in cities where it was banned prior. Paris, Berlin, London, Tokyo, and Washington DC, are among beekeeping cities.

Some have found that “city bees” are actually healthier than “rural bees” because there are fewer pesticides and greater biodiversity. Urban bees may fail to find forage, however, and homeowners can use their landscapes to help feed local bee populations by planting flowers that provide nectar and pollen. An environment of year-round, uninterrupted bloom creates an ideal environment for colony reproduction.

Bee colonies

Castes

A colony of bees consists of three castes of bee:

- a queen bee, which is normally the only breeding female in the colony;

- a large number of female worker bees, typically 30,000–50,000 in number;

- a number of male drones, ranging from thousands in a strong hive in spring to very few during dearth or cold season.

The queen is the only sexually mature female in the hive and all of the female worker bees and male drones are her offspring. The queen may live for up to three years or more and may be capable of laying half a million eggs or more in her lifetime. At the peak of the breeding season, late spring to summer, a good queen may be capable of laying 3,000 eggs in one day, more than her own body weight. This would be exceptional however; a prolific queen might peak at 2,000 eggs a day, but a more average queen might lay just 1,500 eggs per day. The queen is raised from a normal worker egg, but is fed a larger amount of royal jelly than a normal worker bee, resulting in a radically different growth and metamorphosis. The queen influences the colony by the production and dissemination of a variety of pheromones or “queen substances”. One of these chemicals suppresses the development of ovaries in all the female worker bees in the hive and prevents them from laying eggs.

Mating of queens

The queen emerges from her cell after 15 days of development and she remains in the hive for 3–7 days before venturing out on a mating flight. Mating flight is otherwise known as ‘nuptial flight’. Her first orientation flight may only last a few seconds, just enough to mark the position of the hive. Subsequent mating flights may last from 5 minutes to 30 minutes, and she may mate with a number of male drones on each flight. Over several matings, possibly a dozen or more, the queen receives and stores enough sperm from a succession of drones to fertilize hundreds of thousands of eggs. If she does not manage to leave the hive to mate—possibly due to bad weather or being trapped in part of the hive—she remains infertile and become a drone layer, incapable of producing female worker bees. Worker bees sometimes kill a non-performing queen and produce another. Without a properly performing queen, the hive is doomed.

Mating takes place at some distance from the hive and often several hundred feet in the air; it is thought that this separates the strongest drones from the weaker ones, ensuring that only the fastest and strongest drones get to pass on their genes.

Female worker bees

Almost all the bees in a hive are female worker bees. At the height of summer when activity in the hive is frantic and work goes on non-stop, the life of a worker bee may be as short as 6 weeks; in late autumn, when no brood is being raised and no nectar is being harvested, a young bee may live for 16 weeks, right through the winter. During its life a worker bee performs different work functions in the hive, largely dictated by the age of the bee.

|

Period |

Work activity |

| Days 1-3 | Cleaning cells and incubation |

| Day 3-6 | Feeding older larvae |

| Day 6-10 | Feeding younger larvae |

| Day 8-16 | Receiving honey and pollen from field bees |

| Day 12-18 | Wax making and cell building |

| Day 14 onwards | Entrance guards; nectar and pollen foraging |

Male bees (drones)

Drones are the largest bees in the hive (except for the queen), at almost twice the size of a worker bee. They do not work, do not forage for pollen or nectar and have no other known function than to mate with new queens and fertilize them on their mating flights. A bee colony generally starts to raise drones a few weeks before building queen cells so they can supersede a failing queen or prepare for swarming. When queen-raising for the season is over, bees in colder climates drive drones out of the hive to die, biting and tearing their legs and wings.

Differing stages of development

|

Stage of development |

Queen |

Worker |

Drone |

| Egg | 3 days | 3 days | 3 days |

| Larva | 8 days | 10 days | 13 days :Successive moults occur within this period 8 to 13 day period |

| Pupa | 4 days | 8 days | 8 days |

| Total | 15 days | 21 days | 24 days |

Structure of a bee colony

A domesticated bee colony is normally housed in a rectangular hive body, within which eight to ten parallel frames house the vertical plates of honeycomb that contain the eggs, larvae, pupae and food for the colony. If one were to cut a vertical cross-section through the hive from side to side, the brood nest would appear as a roughly ovoid ball spanning 5-8 frames of comb. The two outside combs at each side of the hive tend to be exclusively used for long-term storage of honey and pollen.

Within the central brood nest, a single frame of comb typically has a central disk of eggs, larvae and sealed brood cells that may extend almost to the edges of the frame. Immediately above the brood patch an arch of pollen-filled cells extends from side to side, and above that again a broader arch of honey-filled cells extends to the frame tops. The pollen is protein-rich food for developing larvae, while honey is also food but largely energy rich rather than protein rich. The nurse bees that care for the developing brood secrete a special food called ‘royal jelly’ after feeding themselves on honey and pollen. The amount of royal jelly fed to a larva determines whether it develops into a worker bee or a queen.

Apart from the honey stored within the central brood frames, the bees store surplus honey in combs above the brood nest. In modern hives the beekeeper places separate boxes, called ‘supers’, above the brood box, in which a series of shallower combs is provided for storage of honey. This enables the beekeeper to remove some of the supers in the late summer, and to extract the surplus honey harvest, without damaging the colony of bees and its brood nest below. If all the honey is ‘stolen’, including the amount of honey needed to survive winter, the beekeeper must replace these stores by feeding the bees sugar or corn syrup in autumn.

Annual cycle of a bee colony

The development of a bee colony follows an annual cycle of growth that begins in spring with a rapid expansion of the brood nest, as soon as pollen is available for feeding larvae. Some production of brood may begin as early as January, even in a cold winter, but breeding accelerates towards a peak in May (in the northern hemisphere), producing an abundance of harvesting bees synchronized to the main nectar flow in that region. Each race of bees times this build-up slightly differently, depending on how the flora of its original region blooms. Some regions of Europe have two nectar flows: one in late spring and another in late August. Other regions have only a single nectar flow. The skill of the beekeeper lies in predicting when the nectar flow will occur in his area and in trying to ensure that his colonies achieve a maximum population of harvesters at exactly the right time.

The key factor in this is the prevention or skillful management of the swarming impulse. If a colony swarms unexpectedly and the beekeeper does not manage to capture the resulting swarm, he is likely to harvest significantly less honey from that hive, since he has lost half his worker bees at a single stroke. If, however, he can use the swarming impulse to breed a new queen but keep all the bees in the colony together, he maximizes his chances of a good harvest. It takes many years of learning and experience to be able to manage all these aspects successfully, though owing to variable circumstances many beginners often achieve a good honey harvest.

Formation of new colonies

Colony reproduction: swarming and supersedure

All colonies are totally dependent on their queen, who is the only egg-layer. However, even the best queens live only a few years and one or two years longevity is the norm. She can choose whether or not to fertilize an egg as she lays it; if she does so, it develops into a female worker bee; if she lays an unfertilized egg it becomes a male drone. She decides which type of egg to lay depending on the size of the open brood cell she encounters on the comb. In a small worker cell, she lays a fertilized egg; if she finds a larger drone cell, she lays an unfertilized drone egg.

All the time that the queen is fertile and laying eggs she produces a variety of pheromones, which control the behavior of the bees in the hive. These are commonly called queen substance, but there are various pheromones with different functions. As the queen ages, she begins to run out of stored sperm, and her pheromones begin to fail. Inevitably, the queen begins to falter, and the bees decide to replace her by creating a new queen from one of her worker eggs. They may do this because she has been damaged (lost a leg or an antenna), because she has run out of sperm and cannot lay fertilized eggs (has become a ‘drone laying queen’), or because her pheromones have dwindled to where they cannot control all the bees in the hive.

At this juncture, the bees produce one or more queen cells by modifying existing worker cells that contain a normal female egg. However, the bees pursue two distinct behaviors:

- Supersedure: queen replacement within one hive without swarming

- Swarm cell production: the division of the hive into two colonies by swarming

Different sub-species of Apis mellifera exhibit differing swarming characteristics that reflect their evolution in different ecotopes of the European continent. In general the more northerly black races are said to swarm less and supersede more, whereas the more southerly yellow and grey varieties are said to swarm more frequently. The truth is complicated because of the prevalence of cross-breeding and hybridization of the sub species and opinions differ.

Supersedure is highly valued as a behavioral trait by beekeepers because a hive that supersedes its old queen does not swarm and so no stock is lost; it merely creates a new queen and allows the old one to fade away, or alternatively she is killed when the new queen emerges. When superseding a queen, the bees produce just one or two queen cells, characteristically in the center of the face of a broodcomb.

In swarming, by contrast, a great many queen cells are created — typically a dozen or more — and these are located around the edges of a broodcomb, most often at the sides and the bottom.

Once either process has begun, the old queen normally leaves the hive with the hatching of the first queen cells. She leaves accompanied by a large number of bees, predominantly young bees (wax-secretors), who form the basis of the new hive. Scouts are sent out from the swarm to find suitable hollow trees or rock crevices. As soon as one is found, the entire swarm moves in. Within a matter of hours, they build new wax brood combs, using honey stores that the young bees have filled themselves with before leaving the old hive. Only young bees can secrete wax from special abdominal segments, and this is why swarms tend to contain more young bees. Often a number of virgin queens accompany the first swarm (the ‘prime swarm’), and the old queen is replaced as soon as a daughter queen mates and begins laying. Otherwise, she is quickly superseded in the new home.

Factors that trigger swarming

It is generally accepted that a colony of bees does not swarm until they have completed all of their brood combs, i.e., filled all available space with eggs, larvae, and brood. This generally occurs in late spring at a time when the other areas of the hive are rapidly filling with honey stores. One key trigger of the swarming instinct is when the queen has no more room to lay eggs and the hive population is becoming very congested. Under these conditions, a prime swarm may issue with the queen, resulting in a halving of the population within the hive, leaving the old colony with a large number of hatching bees. The queen who leaves finds herself in a new hive with no eggs and no larvae but lots of energetic young bees who create a new set of brood combs from scratch in a very short time.

Another important factor in swarming is the age of the queen. Those under a year in age are unlikely to swarm unless they are extremely crowded, while older queens have swarming predisposition.

Beekeepers monitor their colonies carefully in spring and watch for the appearance of queen cells, which are a dramatic signal that the colony is determined to swarm.

When a colony has decided to swarm, queen cells are produced in numbers varying to a dozen or more. When the first of these queen cells is sealed after eight days of larval feeding, a virgin queen pupates and is due to emerge seven days later. Before leaving, the worker bees fill their stomachs with honey in preparation for the creation of new honeycombs in a new home. This cargo of honey also makes swarming bees less inclined to sting. A newly issued swarm is noticeably gentle for up to 24 hours and is often capable of being handled by a beekeeper without gloves or veil.

A swarm attached to a branch

This swarm looks for shelter. A beekeeper may capture it and introduce it into a new hive, helping meet this need. Otherwise, it returns to a feral state, in which case it finds shelter in a hollow tree, excavation, abandoned chimney, or even behind shutters.

Back at the original hive, the first virgin queen to emerge from her cell immediately seeks to kill all her rival queens still waiting to emerge. Usually, however, the bees deliberately prevent her from doing this, in which case, she too leads a second swarm from the hive. Successive swarms are called ‘after-swarms’ or ‘casts’ and can be very small, often with just a thousand or so bees—as opposed to a prime swarm, which may contain as many as ten to twenty-thousand bees.

A small after-swarm has less chance of survival and may threaten the original hive’s survival by depleting it. When a hive swarms despite the beekeeper’s preventative efforts, a good management practice is to give the depleted hive a couple frames of open brood with eggs. This helps replenish the hive more quickly and gives a second opportunity to raise a queen if there is a mating failure.

Each race or sub-species of honey bee has its own swarming characteristics. Italian bees are very prolific and inclined to swarm; Northern European black bees have a strong tendency to supersede their old queen without swarming. These differences are the result of differing evolutionary pressures in the regions where each sub-species evolved.

Artificial swarming

When a colony accidentally loses its queen, it is said to be ‘queenless’. The workers realize that the queen is absent after as little as an hour, as her pheromones fade in the hive. The colony cannot survive without a fertile queen laying eggs to renew the population. So the workers select cells containing eggs aged less than three days and enlarge these cells dramatically to form ’emergency queen cells’. These appear similar to large peanut-like structures about an inch long that hang from the center or side of the brood combs. The developing larva in a queen cell is fed differently from an ordinary worker-bee; in addition to the normal honey and pollen, she receives a great deal of royal jelly, a special food secreted by young ‘nurse bees’ from the hypopharyngeal gland. This special food dramatically alters the growth and development of the larva so that, after metamorphosis and pupation, it emerges from the cell as a queen bee. The queen is the only bee in a colony which has fully developed ovaries, and she secretes a pheromone which suppresses the normal development of ovaries in all her workers.

Beekeepers use the ability of the bees to produce new queens to increase their colonies in a procedure called splitting a colony. To do this, they remove several brood combs from a healthy hive, taking care to leave the old queen behind. These combs must contain eggs or larvae less than three days old and covered by young nurse bees, which care for the brood and keep it warm. These brood combs and attendant nurse bees are then placed into a small ‘nucleus hive’ with other combs containing honey and pollen. As soon as the nurse bees find themselves in this new hive and realize they have no queen, they set about constructing emergency queen cells using the eggs or larvae they have in the combs with them.

Animal welfare

Vegans may view the consumption of honey as cruel and exploitative with modern beekeeping a form of enslavement. Once the honey is harvested, it is common practice to substitute the bees’ natural food store (i.e. honey) with sugar or corn syrup in order to maintain the colony over winter. There is disagreement amongst groups about the extent to which all animal products, particularly products from insects such as honey, must be avoided. Neither the Vegan Society nor the American Vegan Society considers the use of honey, silk, or other insect products to be suitable for vegans, whilst Vegan Action and Vegan Outreach regard that as a matter of personal choice